From April 16-27, 2025 Harrison and I attended a 10-day Vipassana meditation retreat. My third of this kind, and his first.

The word Vipassana means “to see things as they really are”. It is the form of meditation discovered and practiced by the Buddha around 2,500 years ago. Vipassana is concerned with the truth of what is happening to us at the level of bodily sensation. The first stage of learning the technique is to discipline the mind enough to be able to feel subtle sensations on the surface of the skin that we are not normally able to feel but are in fact happening all the time.

The idea is that bodily sensations mark the entry of a stimulus to one of our sense doors (sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and the mind). First, our senses “cognize” that something is happening, from there we “re-cognize” (ie: sort the sensation into a category based on past experience – for example words of praise = “good”/criticism = “bad”) and from there we generate a sensation. The purpose of the practice is to develop an “equanimous” (calm and composed) mind – fully feeling our sensations, while developing the ability to stop reacting to them.

Over time – observing our sensations – including an entire range of sensations without reacting, we begin to learn how our mind works. For instance, on the retreat I was able to observe how much my mind is caught in past and future thinking.

One of the things I deeply appreciate about Vipassana is that it is a scientific method.

So too is the science of society, our method for making social change – dialectical and historical materialism. (Dialectical: understanding things in their relationships to each other. Historical: societies grow, develop, and change based upon how the means to life are produced and distributed and the associated relations. Materialism: There is an objective reality, and the world and its laws are knowable. “It is not the consciousness of man that determines their conditions but their social conditions that determine their consciousness”)

What are some features of this “science of society” that also appear within Vipassana?

Like Vipassana, the science of society holds that all things are interconnected, inter-related and co-determined. Nothing can be understood in isolation. This is the dialectical method, which is concerned with the relationships between things.

Also like Vipassana, the science of society upholds the idea that change is a constant. Everything is in a state of arising and passing away. This was the insight of Siddhartha Gautama (known as the Buddha) 2,500 years ago who “discovered” atoms well before atomic theory through observation of the body.

“All nature,” says Engels, “from the smallest thing to the biggest, from grains of sand to suns, from protista (the primary living cells) to man, has its existence in eternal coming into being and going out of being, in a ceaseless flux, in unresting motion and change.” Building on that, dialectical and historical materialism shows that as in nature, so in society, an accumulation of quantitative changes (changes in degree) give way to a qualitative change (change in kind/form). Think of water reaching a boiling point and transforming into gas (or a freezing point, and transforming into ice).

Another echo of Vipassana that overlaps with dialectical and historical materialism is getting below the surface of things to reveal the ulimate truth of mind and matter. This is the goal of the practice. In the method of the science of society, we have to understand not only the “limbs and leaves” of the problem, but also – and chiefly – its root.

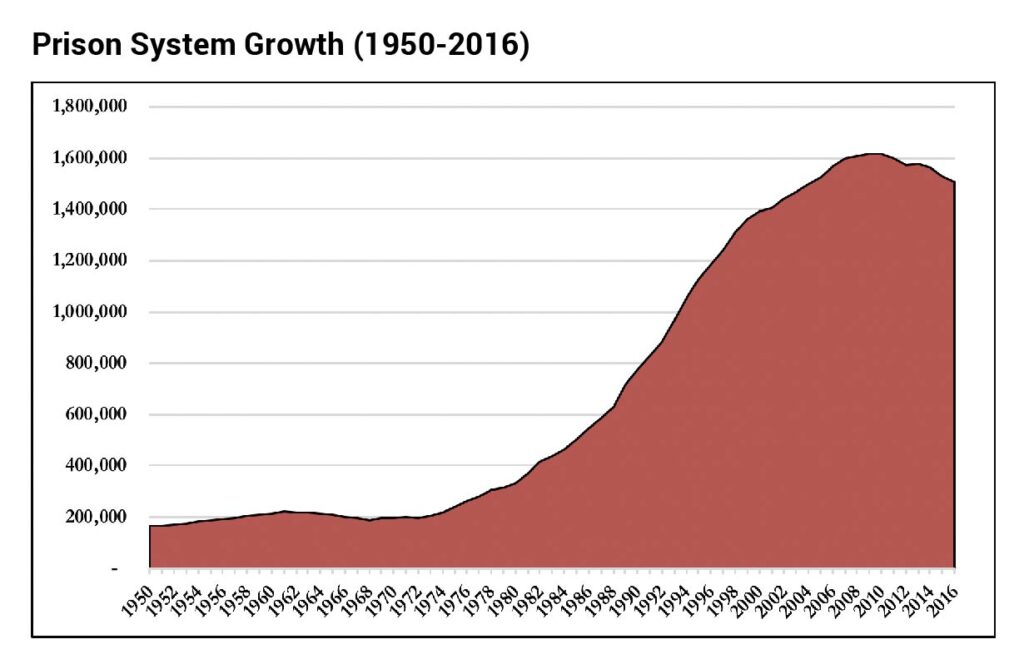

For example, if we apply dialectical and historical materialism to the problem of over-policing and mass imprisonment we understand that it won’t work to “abolish” police and prisons without abolishing the system which produces increasing poverty and misery that criminalizes our very survival. The problem is not simply what is visible at the surface.

What makes Vipassana a way of life, and not a religion is that it puts a premium on practice and direct experience, not just “believing”. This is the whole purpose of the meditation – to transform your mind from reactivity by applying the method, not just by “willing yourself”, praying, hoping, or wishing, but by practicing. Faith and belief are important, and are the foundation of our commitment to practice, but alone, they are not enough. Similarly, for scientists of dialectical and historical materialism, practice is essential. Our work must go much deeper than “convincing” people of things or “winning” people to a line. People agree to lots of things that are written down on paper, but those concepts and ideas don’t necessarily govern their behavior. We see this all across our movement, to the great detriment of our prospects for ultimate victory.

S.N. Goenka, the incredible teacher who popularized Vipassana in the West, tells a common story that we can all relate to. We leave the funeral of a loved one, newly conscious of how fleeting and fragile life is. We are determined to no longer waste time, to let our baggage go, to be present in every moment. We feel transformed – but the feeling ends. 24-28 hours later we are back to the same old habit patterns, living in the past and future, caught up in cycles of reaction. Why? Because we simply don’t know HOW to do things differently. In our movement to abolish poverty led by the poor, organization is the best laboratory for experience. Not mobilization, not training, but organization. Organization creates the conditions to build unity and solidarity across difference through engaging in a common struggle and learning and leading together. Organization enables collective work. Organization requires learning how to communicate, collaborate and repair harm. Carrying out the “program” takes primacy over agreeing with it. Theory must be applied and gains relevance chiefly in its application.

Another echo between these two scientific traditions involves the contributions of their chief architects. Siddhartha Gautama on the one hand, and Karl Marx on the other. There were many enlightened teachers before Siddhartha, and many after. Many before had talked to followers about transcending the cycle of craving and aversion by clearing the mind, or focusing on an image or mantra. But it was Siddhartha that evolved this thinking to the next level, and made it an actionable tool for personal liberation through the scientific method of deep examination of the body. Likewise, there were political economists and philosophers before Marx who made critical contributions that he learned from and built on. But it was Marx who worked with and deepened concepts of those who had come before him to make a coherent theory and actionable approach to class struggle. He set the stage for the working class to begin to practice for the sake of changing the world.

Accepting the reality of constant change doesn’t mean resigning oneself to genocide, war and denial of our right to live. In fact, it must mean that we remain flexible, adaptable, constantly open to new possibilities that are emerging. The law of nature discovered by the Buddha is an ancient science that still applies today. The law of the science of society arises out of the historical epoch that began approximately 500 years ago and has now reached its peak. Both of these scientific methods ask us to pay attention to that which is arising, though it may still be incipient. We need both ancient and Indigenous knowledge and the knowledge of the science of society for human liberation. Human liberation is both individual and collective. There can be no individual liberation without collective liberation. There can be no collective liberation without class struggle.

On his birthday 5.21.25, dedicated to my mentor, Willie Baptist

More on Vipassana:

https://www.dhamma.org/en/index

More on dialectical and historical materialism:

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1938/09.htm